Interfaces made of light

Thoughts on the future of computing and the challenges of creating interfaces made of light.

This is the second story in a series where I explore the challenges and opportunities of designing for advanced technology products.

The software we live in

We spend more time in the software we use than the buildings we occupy. We talk, think, create, date, meet, learn, laugh, and work through the interfaces displayed on our black rectangles.

Yet, most of the software we use and make is based on decades-old constraints and assumptions about what a computer can and can’t do. Ideas once groundbreaking now feel stale and rigid. Bret Victor poignantly made the same argument in his paper Magic Ink from 2006:

Today’s ubiquitous GUI has its roots in Doug Engelbart’s groundshattering research in the mid-’60s. The concepts he invented were further developed at Xerox PARC in the ’70s, and successfully commercialized in the Apple Macintosh in the early ’80s, whereupon they essentially froze. Twenty years later, despite thousand-fold improvements along every technological dimension, the concepts behind today’s interfaces are almost identical to those in the initial Mac. Similar stories abound. For example, a telephone that could be “dialed” with a string of digits was the hot new thing ninety years ago. Today, the “phone number” is ubiquitous and entrenched, despite countless revolutions in underlying technology. Culture changes much more slowly than technological capability.

20 years ago Victor made two observations. First, the interface modalities demoed in the 1960s by Engelbart have seen little change. This feels like a missed opportunity when considering the advances of technological capabilities. Computers are much more powerful, but our interfaces are not. On the other hand, it may simply be the result of Darwinian evolution of software. Terry Winograd once told me these interfaces are abundant exactly because they work so well. Like the shark that’s been around for 400 million years, largely unchanged, our computing metaphors and user interfaces may have reached a plateau exactly because they work the best for our current cultural environment. Billions of people have been trained in using desktop UIs, point-and-click devices, self-contained apps, and abstractions like files, folders, and login. Habits are hard to kick.

Victor’s second observation is more subtle, “Culture changes much more slowly than technological capability.” The pace of culture is much slower than infrastructure. Our computers may run 1,000,000× faster, but our culture certainly doesn’t. Our human ability to manage the abstract nature of computers hasn’t evolved to the same degree as the underlying compute substrate, despite the fact that so much of our lives are mediated via the computer. But what if we could change that?

This is a story about breaking user interface constraints and rethinking what a computer is, and how we might interact with a computer through interfaces made of light.

Light as interactive paint

In 2014 I joined a small team inside Google called Replicant. It was a robotics cluster guided by Andy Rubin who had founded Android and sold it to Google a decade earlier. Rubin and the team had snatched up a dozen robotics companies from around the world including Boston Dynamics and Schaft. One of the most creative robotics companies was Bot & Dolly founded by Jeff Linnell and Randy Stowell.

Bot & Dolly used robots to do something unexpected. Instead of moving boxes around a warehouse they had instructed the robots to make cinema. The team had developed custom software to control industrial robotic arms and hooked them up with camera rigs that allowed directors to control the camera movements with extreme precision.

Not only that. The team had also experimented with projection mapping to create stunning visual effects outside of the bland CGI parameters. New technologies breed new kinds of artists.

Their most famous production is the above video, Box. It showcases the two characteristic technologies of synchronizing robot-with-camera and projection mapping to create the (in-camera) illusion of depth of field and 3D objects floating in space.

Today, there’s a host of firms offering robotic camera rigs. But back in the early 2010s B&D led the way in experimenting and showcasing the ensemble of robots in creative pursuits. Projection mapping proved especially tricky and really only suitable for large stage shows and static displays where you could control the environment. You could experience it in theatrical spectacles like whole building animations or big DJ sets. If the projector got mis-calibrated the whole illusion would break. But if you could somehow dynamically map the world in real-time and then update the projection to match, it felt like magic.

Adjacent to the robotics projects we wanted to explore this dynamic medium for a different kind of computing experience. One where traditional screens would get in the way of the work at hand. We created project Big Wave, named for the alluring and dangerous big waves off the coasts of Hawaii and California. The idea was a computing interface where a surfboard shaper could visualize his work before and during shaping a surfboard out of the foam core.

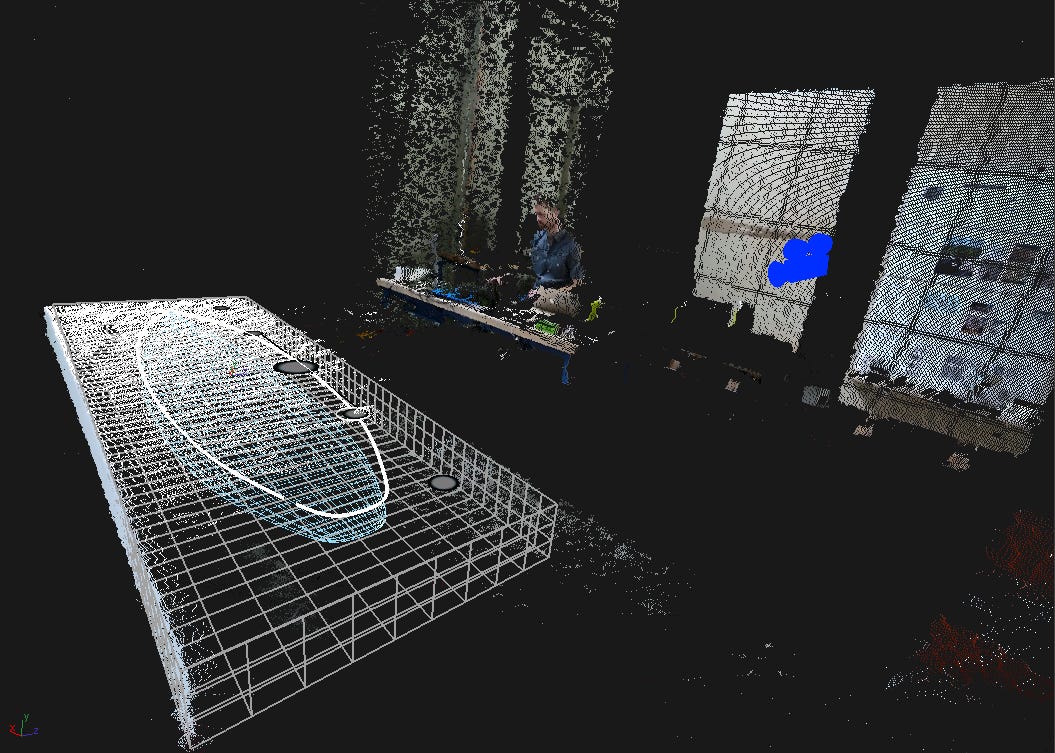

We wanted to visualize the 3D board floating “inside” the foam block. The talented creative technologist, Phil Reyneri, created the whole setup which was a mix of three elements. First, three overhead projectors would project on three sides of the foam core. This created the illusion of seeing through the material in three dimensions and helped with shadows and occlusions. Second, a motion and depth-sensing camera (a Kinect in our case) would sense the objects, position of the user, and track his eyes in 3D space. Third, a piece of control software would register changes and change projections accordingly. Input. Output. Control.

The Kinect camera made it feel dynamic and magical. The software would perform a structured light scan to precisely map the light onto the substrate and then calibrate distortions. Not only could the system project on a 3D surface, it could now keep track of depth and position in real-time. That allowed Phil to add user gaze estimates to the projection. That meant the software could distort the projection based on where the user’s eyes were and create a realistic 3D object on 2D surfaces. Obviously, this would only work for one person at a time (and it’d look broken for any onlookers). But it demonstrated an impressive user freedom since the user didn’t have to wear any special glasses or head-mounted displays to experience the effect. Move your head around and see a different perspective; realistically projecting a virtual surfboard onto a block of foam.

In the video above you can see the Kinect camera mounted on the wall between the surfboards. It’s tracking Phil’s position and his eyes (and inferring rough gaze direction based on the size and distance between his eyeballs.) He’s holding up his phone camera next to his eyes to record the effect. No special glasses or other gimmicks. The projection snaps into place as he approaches. It looks stunningly realistic with very little lag and only struggles in the end bit where the Kinect can’t track his eyes properly. Notice how the blue wireframe lines of the board distort to give the illusion of perspective change.

This setup of light as dynamic paint output and user position and gaze as inputs demonstrates a radically different computer interaction than the ones imagined with flat screens and virtual windows in the 1960s. No square screens to cage your thinking, no plastic controllers to change what you see. Just walk up and move your head to look around. Like in real life.

This effectively augments the object at hand. Let reality simulate physics. It paints computing directly onto the world we inhabit. But just tracking gaze is a pretty limited interaction modality. And computers can do a lot more when you can directly manipulate them. For the next demo, Phil moved the Kinect camera to track a puck. A small piece of plastic with a retroreflective sticker on top. This allowed him to use the light tracking as a means of input. Based on the puck’s position in space, it would “snap” to points on the interface. Like moving the Bézier curves at a 1:1 ratio on the foam board. If he lifted the puck off the foam core it’d “detach”. Cleverly imitating how real-world objects work. Unlike most VR demos where the virtual tool (e.g. screwdriver) is a simulacrum of a real tool, devoid of any realism like weight, torque feedback, or feel. And since it’s still tracked as a virtual object, the user can also move it to an “action area” that would change the puck’s function unlike a real object. Best of both worlds.

This prototype also shows another important aspect of using light as a computer interface. You can in principle use any tool on any substrate to control the computer. Our hands are incredible extensions of our body. They provide a lot more subliminal feedback and nuanced inputs than we care to design for today. We’re grossly numbing our ability to interact with computation by mediating it through dead glass or point-n-click devices. Let alone tapping our fingers in mid air. Handwaving is just not the same as sensing real friction.

In the Big Wave demos we can use any tool, like sand paper, carving tools, paint brushes, or masking tape, and identify them via object recognition and assign a specific software action to it while maintaining the original tool use. This would allow the user to use the tool directly instead of fiddling with a virtual model of the tool on a 2D surface first. For example, a surfboard shaper could use various shaping tools that each would cast a different visual or measurement to help him get his work done – without learning how to use a computer program or switch context from the real to the virtual world. The interface middle layer disappears.

The demos showed object-tracking as an input-modality, both to find the user’s position and his gaze in 3D space and to analyze the current shape of the projected substrate and tool types. If the user were to alter the substrate, the computer would automatically compute the changes and re-render the visuals. In our example the surfboard shaper would shave off parts of the foam manually and then allow the computer to visualize stability zones, feet positions, or fluid dynamics right on the foam core. No need to leave the workshop and open a complicated 3D virtual model inside a simulation tool. The world is already simulated.

I don’t think a surfboard workshop is the ideal first place for these types of interfaces though. But it made a simple and compelling demo. White foam offers good reflection and who doesn’t love a good fluid dynamics animation? Instead, imagine a biology lab with 100s of separate test tubes, incubation beds, vials, tools, and instruments, each object visually lit up, highlighted with timers, contextual info, and experiment sequence on top of the work bench. Or a factory assembly line with robot carts wheeling around, 1000s of objects to be assembled, some by robot, some by hand. Humans can latently coordinate with robots via the projection and better coordinate complex interactions. Or a busy airport, tracking individual travelers and displaying their exact gate and path just for them on the floors throughout. No need for AR apps for personalized way finding. The options are endless. The idea here is not to replace powerful purpose-built software programs. Instead we wanted to demonstrate what’s possible if you expand the range of interfaces just using light. Ideally, lower the barrier of entry, remove the manipulation-by-proxy, and make computing ephemeral and users freer.

Escaping flatland

Humans are ingenious. We can solve really, really hard problems. Abstract, novel problems that span centuries to solve. Yet, I can’t help but wonder if turning the computing experience into an ever more siloed and simulated experience is hampering our ability to do this?

Our current computing environment forces us to collaborate in a rigid and twisted way. Regardless if it’s mediated via a normal monitor or a Virtual Reality headset, the underlying computing environment is the same. “Real-time” collaboration in software just means a tight loop of sequential updates to a database. Even if the UI shows two cursors moving on a screen at the same time. Typically this results in endless human meetings to make sure the humans are in sync as well. Not ideal.

VR doesn’t solve this. It just transforms our 2D environment into a 3D environment based on the same underlying interaction ideas. Today’s head-mounted virtual reality interfaces still look like boring 3D versions of the interface ideas Engelbart pioneered eons ago. Slicker, brighter, and glassier. But ultimately the same computing interface substrate. Our culture seems stuck in a local maxima. Unable to escape the floating-windows, point-n-click, screen-first world invented in flatland. The normally tantamount human face-to-face interactions are perverted into simulated avatar video calls while we sink further into isolation and sameness. The tech is impressive but the culture is not.

I’d argue VR is a stop-gap solution1. It’s burdened by the same interface constructs as your laptop while isolating and limiting collaboration outside the virtual space. Even more so than staring at a screen together. It creates a thicker barrier to explore the real world than a smartphone does. Literally limiting your field of view and natural ability to perceive nature’s color, shadows, subtle movement, and distant sounds. It may work great as a TV or game console, not so much for exploring and understanding the world we live in. VR also removes understated cues from our innate apparatus to collaborate, like eye contact, body language, subtle sounds, and group dynamics. This suppresses our collective ability to reason, understand the world, and persuade each other. You simply can’t sense presence or aura of other people when plugged into VR. When the world is mediated through a simulation, everything gets compressed as a simulacrum of the real thing. Entering a simulated world cultivates a very different social fabric; one with expectations of constant entertainment and saturated single-player aesthetics. But actual progress happens in the real world. We run experiments, test hypotheses, talk to people, build prototypes, and measure reality by venturing out of our software worlds and into the real.

What if we could create an ephemeral computing experience where users never had to learn about processor specs, installation packages, keyboard shortcuts, or memory management? What if a child could pick up a thing in the world and just ask a question and get a richly detailed and visual example right there? Today’s scattered interaction modalities with computers seem so archaic and crude when you know what’s possible.

Why hasn’t it happened yet?

One major problem of projection mapping as a dynamic medium is projection quality. In a brightly lit room or outdoors the projection simply fades out making it near impossible to see. It’s hard to compete with the sun. And the physics makes it much harder to project on large rough surfaces than small reflective surfaces. The further the light has to travel, the dimmer it gets.

The now defunct Lightform’s Project LFX demonstrated a commercial version of a dynamic room projector. The video below (also featuring Phil Reyneri) shows a self-contained device with voice as input and projection as output. Instead of installing multiple projectors, a single ceiling mounted projector would paint the relevant UI on top or next to the object in question. Just talk to your “room assistant” and it would display relevant info on objects. Say your morning run on a map on the wall or a coffee bean order next to your coffee machine or even a simulated board game on your coffee table.

The hardware is pretty novel with a swivel mirror to direct the projection around the room and a built-in motion camera to track occupants. But the foundational interaction ideas are lacking. It’s just your phone UI projected on the wall. It’s hard to see how this is radically better. Also, the illusions are hard to master when projecting on less forgiving surfaces like the flat brown coffee table. Here, a VR headset wins on illusion quality.

Another issue is tracking. Projecting on anything other than static items requires very fast tracking input and output. While tracking has become really good (as shown in the above video) it still requires a lot of bulky hardware to make it work. To keep the makeup illusion robust, the whole area (not just the face) has to be lit up. It’s more gimmick than viable computer alternative. But we’re getting closer.

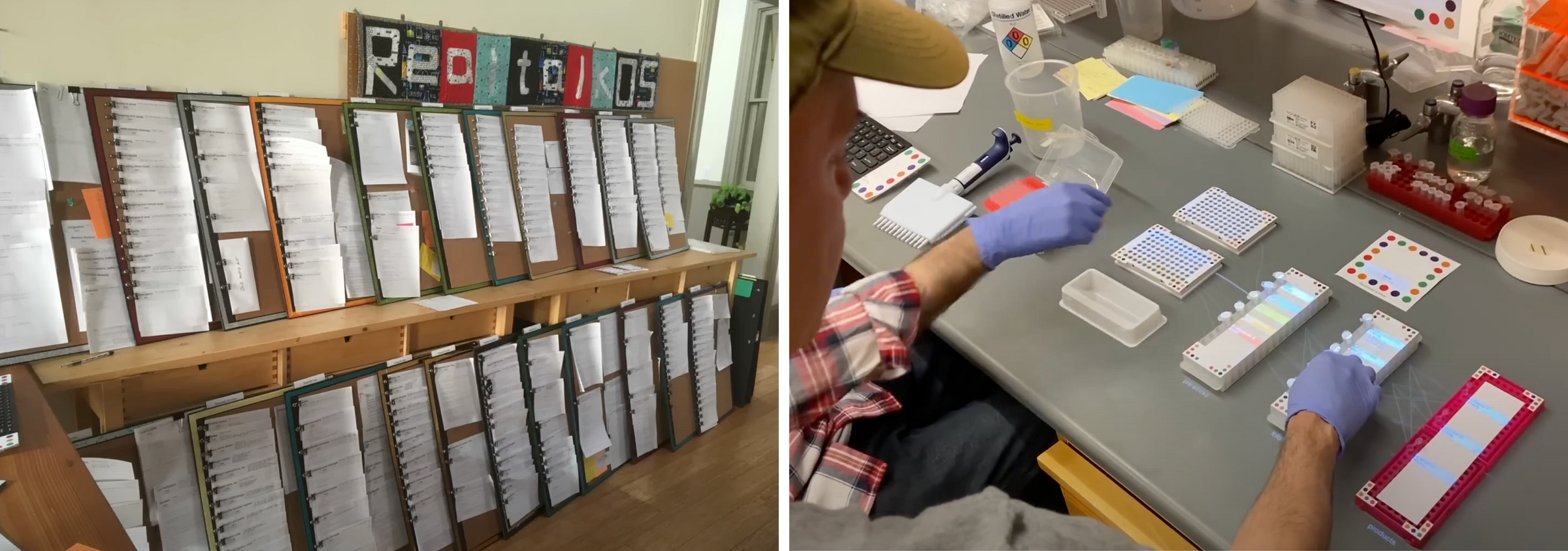

At the same time we fiddled with demos in 2014, Bret Victor set out to actually make it real. He founded Dynamicland, a non-profit research lab investigating a dynamic medium based on the principle of a humane representation of thought. He posited that our computers are inadvertently limiting our abilities to think and explore abstract concepts together. The very nature of our computing tools limits what we can imagine and accomplish.

In my opinion Victor is the most original software designer of our generation. Don’t let the janky visuals and the shelves stacked on soup cans fool you. The vision is radical and the ideas are powerful. I encourage you to explore the work on your own.

Victor explores what it would mean if we could use computing as an expressive medium in addition to text, pictures, sound, and video. Create the foundation for “computation as electric lighting” via a new “programming system”. Available everywhere, whatever you need to do. Let anyone use computing to express and explore ideas. This paradigm effectively inverts the computing experience; instead of you looking into a black box, the computer projects out onto the real world. This dramatically lowers the barrier to explore ideas together. Not by wearing a headset or looking at a screen or projecting static info on a wall. But by allowing everyday objects to become enriched with computing, a new form of interaction emerges; the communal computer. Everyone can see what everyone else is working on and change and modify it in real time. No programming skills required. Objects are enriched with computing, not simulated inside a specific device.

The concepts expressed in Dynamicland are pretty profound. Software, including the operating system, now lives on printed paper pages instead of a hard drive2. The instruction set is controlled by papers covered in dots to instruct the computer (via cameras) which in turn projects the desired interface onto the real world. The departure from our current computing paradigm is apparent. No more desktop metaphors or touch screens. Dynamicland is a research endeavor unbounded to explore the edges of computing idea space.

But it’s still research. Actual commercial devices are not available yet, and the room setup requires us to rethink the entire space, not just a single device. More like a lab than a laptop. But must this dynamic medium live in a room? What if we could create a self-contained unit, similar to a smartphone, you could bring with you and explore the real world?

Go small or go home

If we ignore the whole room experience for a minute and instead focus on a wearable projector experience, we open a whole host of other possibilities and challenges. Pico laser projectors have been around for a while and can actually project focus-free and occlude black areas much better than traditional cinema-grade projectors, making basic interface visuals higher contrast and easier to render and read. They also require much less power per lumen.

The medical device, the vein finder, is a good example of a clever mobile use case. A medical professional who needs help finding a vein can use the scanner to locate hidden veins underneath the patient’s skin. The device uses a deep infrared scanner to locate the vein and then shows the veins’ position using a green laser projector directly on the skin, again 1:1 mapping the digital to the physical. The body has become the substrate for interaction. This type of tech could be used in lots of medical scenarios; like mapping the fetal position of the baby onto a mother’s pregnant stomach, or aiding surgeons and staff to conduct complex procedures in the operating theatre, or just elucidate the hidden inner workings of the body to children visiting the doctor’s office. No touch controls, no screens, no heads-up displays. Just light.

This brings me to the much hyped Humane AI Pin which also included a pico laser projector. The philosophical departure of the Pin was a post-smartphone world where we would talk directly to our computers instead of staring at pixels on a screen. Similar in spirit to the Big Wave demos and Dynamicland, the team at Humane wanted to envision a future free from screens.

The main problem of removing the screen, however, is that you now rely a lot on audio as input and output. This puts pressure on your audio user interface (AUI) to be as good or better than a graphical user interface (GUI). As if you suddenly go blind, your other senses must compensate. And while voice interaction modalities have come a long way since the advent of transformers and can be great at allowing the user to give voice commands as inputs, it’s typically pretty bad as complex voice output. A voice interface is typically a poor substitute for a user to explore options and faceted menus. (Anyone who’s ever had to deal with a dumb support call bot endlessly reading out menu items, knows what I’m talking about. Neither fun, nor fast.)

Visual scanning is just so much easier than listening when mentally mapping information to meaningful concepts. Thus, Humane included a small laser projector and depth-tracker in their device meant to display basic menus and texts and let you use your hand motion to control the interface. Very clever idea. If it works.

The problem again is the robustness of the interaction. The Verge review does a good job testing the interaction. Compared to modern smartphones, where we’ve become so accustomed to swipes, scrolls, and quick taps (on glass), to the point it’s become second nature, a projection mapping interface like this presents an extreme departure and steep learning curve. Not only is your palm now the screen, your hand position is also the controller. You better have excellent motor control skills. And philosophically we didn’t even get rid of the screen! We just moved to a lesser form factor that once again lives in your hand. One step forward, two steps back.

Let’s ignore all the hardware issues of this Gen 1 product, and just focus on the laser projector and its interface challenges. Firstly, the low-power laser projected in green color only. But displaying only one color makes it much harder for the user to distinguish hierarchies and separate info from actions. Even the first black-and-white Mac OS used thicker button outlines, background patterns, and icons to guide the user and help her separate hierarchies and establish ontologies. Remove all that and it becomes hard to understand what you’re looking at. This is less of an issue if all options are simple binary choices, but in the demo they seem much more complex with multiple button options, circular scrolling, and linearly stacked cards. Secondly, the interaction is based on depth, forcing the user to rock (and roll) their hand to navigate the interface. The subtle differences of hand tracking in the “palm roll” is cool in demos but such delicate manipulation just doesn’t work in practice. Imagine doing this when it’s raining, cold out, you’re tired and just want to call that Lyft and get home. Buttons with tactile feedback really do work well in adverse conditions.

But let’s set aside the brittle interface ideas and unpolished implementation. The main issue I have is that it just doesn’t seem necessary. It seems to violate the iron rule in consumer technology; do not introduce new interfaces without a killer use case.

The physical touch pad on the device itself seems plenty adequate for controlling music, taking photos, or invoking translations. And we all already know how to interact with glass touchpads. For more complex options like settings, sending text messages, or creating actions, you’d want to invoke the voice modality anyway. That’s the whole point of a screen-less future, right? And for those few instances where you’d need to “type” in sensitive info like a credit card number or a password, why not just use the camera or a fingerprint reader? Let the AI figure it out. And if your AI isn’t good enough, a home-made nested navigation displayed on a monochrome laser projector in your hand won’t save you. That’s just a worse screen. Instead it should do things a screen can’t do.

For example it’d be nifty if the Pin could point to stuff in the real world like a laser pointer. Much faster and simpler than trying to describe it via audio only3. Imagine you’re walking down the street, stop at a wall of show posters and ask the Pin, “book me tickets to this one.” Now, instead of the pin blurbing out all the names or visuals it sees to confirm which show you’d like tickets to, it simply shoots a laser pointer dot to the poster it thinks you mean (or the one you pointed to). It can just ask “this one?” and you tap confirm or say “yes.” This type of hybrid interaction between pointing (fingers and laser) and talking is much more powerful than either alone. Humans do it all the time!

Laser projectors can so much more than show boring 2D UI graphics. Why not simulate the unseen, like plant growth, illuminating flowers and animals, or just create small delightful moments in the world (like the 10-year-old video below). I’d bet kids would love to venture out in the woods and explore with that kind of device.

It’s easy to criticize and hard to build. I’m extremely impressed that they shipped this device at all. Laser projection is notoriously difficult to work with. Especially on a wearable device that’s constrained by battery, size, cooling, and BOM costs. Making new types of hardware is hard. Let alone a whole new computer paradigm. Humane’s vision is compelling and it takes real courage to break the mould and execute on novel technologies. I wish they survived for a second version.

Culture fit

The vigilant designer’s first question should be, how is this radically better than the alternative? How is this technology going to overcome social inertia and cultural resistance? Even if the Humane Pin had to slightly bend their vision of a screen-free experience, drop the projector idea, and piggyback on an iPhone app to get off the ground, I think it would have been worth it. Most discrete tasks are simply better on screens. And don’t forget, people love their smartphones. They keep growing in size every year. “Liberating” people from their screens is not a compelling mission in and of itself. The technology has to offer something better. A different future that’s additive, not subtractive. The PC is still here despite the smartphone’s overwhelming success. As I stated in the beginning of this essay, our lives are mediated through software, yet limited by the pace of culture.

The original sin of many advanced tech products is that they presume a consumer culture where none exists. Google Glass also had the right product idea, but got the culture question wrong. The public simply wasn’t ready. The glasses were presented as the next post-smartphone device for the masses. The tech was very impressive for the time; an ultralight augmented reality display, simple voice operation, and features like Google Knowledge assistance, navigation, and video recording. But force feeding an advanced technology product to the mainstream consumer, ruined the adoption and created the infamous “Glasshole” memes. Today, it’s clear the culture has shifted with the success of Meta’s larger, clunkier Ray-Ban smartglasses. And yet, they look like regular sunglasses from the 1950s. Culture moves slowly.

Culture is the invisible hand that drives technology adoption and success. Not feeds and speeds. Sure, the tech needs to be ready; high quality and work reliably. But adoption starts with culture. And culture starts with compelling stories and use cases. Think clearly about what your product does at least 10× better than the alternatives. Remember, an interaction itself can be magical. Like when Steve Jobs famously introduced the first iPhone and he remarked the eponymous line from an impressed board member, “You had me at scrolling”. That is story. The team didn’t innovate on the concept of the contact book. They didn’t have to. Simply the experience of scrolling through a list with physical inertia built-in felt spectacular at the time.

The prototypes above were made over a decade ago. With off-the-shelf projectors and crude demo setups. They look dated compared to the advances in game-engine graphics and gleaming VR worlds we have today. But the underlying ideas are extremely powerful and offer a much brighter avenue for the future of humane computing in my view. But we’re still early. We still have lots of missing pieces left to invent and refine. VR seems like a stop gap solution to the problem of computationally augmenting our reality. It comes with severe drawbacks, and yet the pull of augmenting our world with simulation, ideas, and beauty is alive and well in our culture. Maybe GenAI will allow on-the-fly UIs to work in this new modality? Maybe we need AI voice agents to become better? Maybe we’re finally on the brink of a new computing paradigm?

Maybe, just maybe, the computer will not look like a computer in the future. Maybe it will be made of light. Wouldn’t that be something.

Virtual Reality (VR) is typically understood as a fully simulated reality, where the device renders every pixel and blocks out stray photons to maintain the illusion. Augmented Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR) are currently understood as hybrid simulated devices, allowing the user to see through a pair of glasses that shows photons from the real world and overlay only parts of the view. Apple Vision Pro and Meta Quest are VR, whereas Google Glass, Microsoft Hololens and Meta Ray-Bans are AR. Regardless of display technology they all require the user to put a computer on her face to experience spatial computing. In contrast projection mapping doesn’t.

I’m not sure how feasible going all in on paper is. Abstracting away the computer code has wonderful benefits. Going back to actual paper files and folders seems like an unnecessary step backwards. But I applaud the raw dedication to the idea of making computer code communal and being able to spatially view the code outside any kind of hardware.

Understanding audio as a robust interface modality is outside the scope of this essay. But suffice to say that describing abstract qualities or positions in 3D space using audio only, feels a bit like the game “pin the donkey”, where children, struggling blindfolded, try to pin a tail to a paper donkey. Close but not exactly. We simply don’t have the elaborate vocabulary to describe all the qualia we can perceive and imagine. I’d argue that once the audio latency is low enough (<800ms) and nuanced AI comprehension is robust enough (how about a humor setting?), voice as a modality will become much more dominant. And then there’s the cultural aspect. Far from all cultures like to be loud. Many Asian and Northern European cultures find it rude to talk in public, let alone have a speaker blasting in public. From this perspective the a screen made of ligth does make sense.