How do you design a self-driving car?

Design lessons from developing the Lyft Level 5 autonomous vehicle.

This is the first story in a series where I explore the challenges of designing for advanced technology products.

In 2018 I joined Lyft to work on their newly-formed autonomous vehicle division called Level 5 (L5 for short). The name was a pun on self-driving capabilities. L1 being completely manual, L5 being completely autonomous. The division had just been created inside Lyft and around 30 engineers had been hired to solve the monstrous task of creating a car that could drive itself.

This is the story of how we designed the tools and hardware for the Lyft self-driving car. My aim is to elucidate the often hidden challenges designers and engineers face when making something that hasn’t been done before. The rocky road of breaking down nebulous challenges and creating elegant and robust solutions for the real world.

I strongly believe we need more designers tackling hard tech challenges. The really important problems in our world exist in the messy real world, and design absolutely has a role to play. Design is not just marketing or the polish at the end of the development process. Design is the development process. Good design offers a path through the maze. It helps teams deconstruct the hard and complex challenges and deliver a working product that makes the product faster, safer, cheaper, and just plain attractive.

And yet, some of the most important lessons when developing novel deep tech products get lost to history. The public sees the finished product and the slick marketing campaigns. This is a story of how you make something out of nothing. A rare peak behind the curtain of how we designed the self-driving car. Strap in and let’s go for a ride.

Make the car see the world

The first step was to get a suitable car we could hack so it could see the world and auto-steer. We needed sensors to see the world, compute-systems to predict traffic and steer the car, software to manage and annotate all the data, safety testing, ops drivers, data lablers, mapping teams… The list was long and we were late to the party. The core problem was how do we sense enough of the world, fast enough to make decisions in real-time? Driving is inherently a hard challenge. Even for humans, hence we have driving schools and lots of regulations.

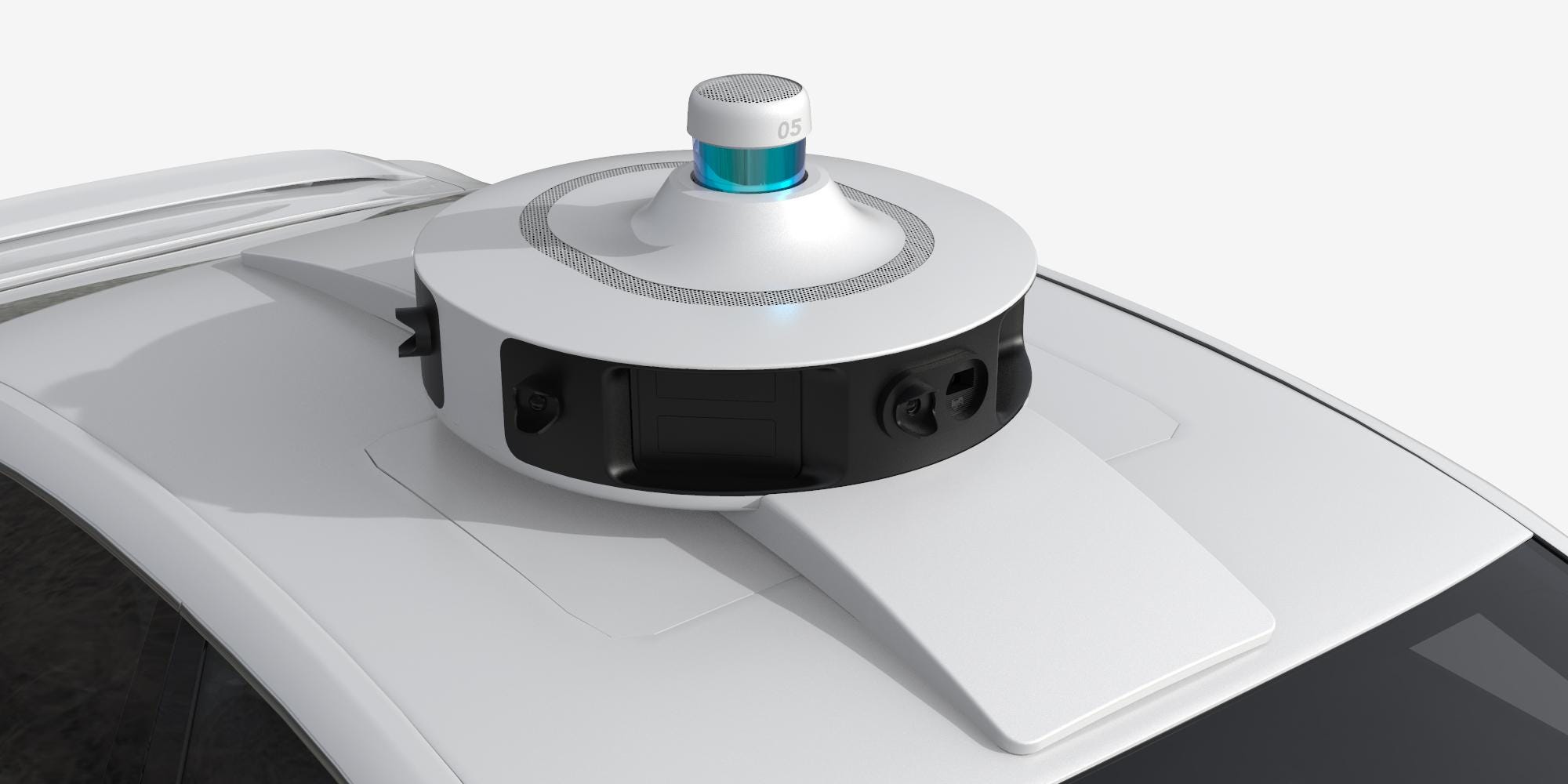

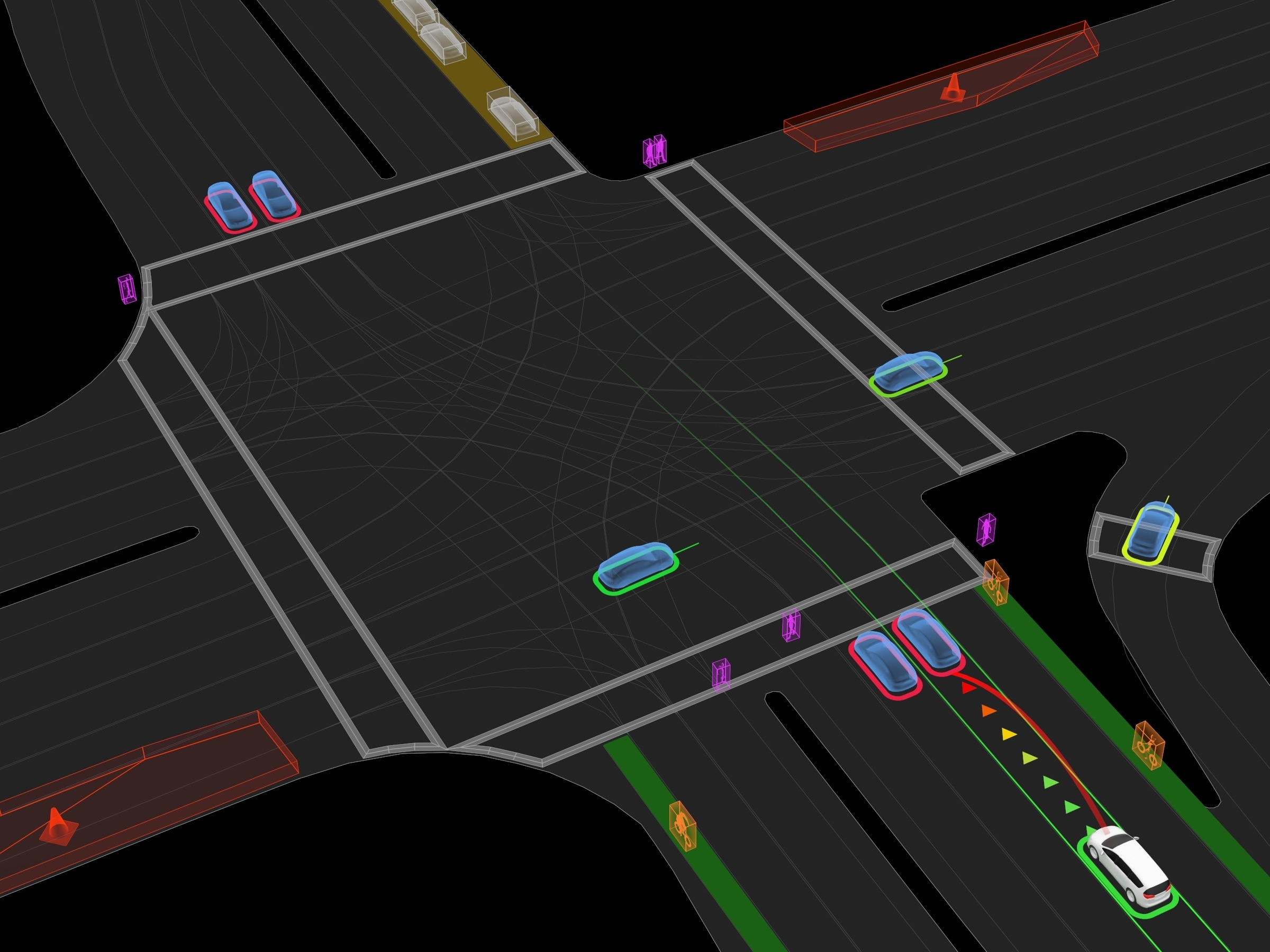

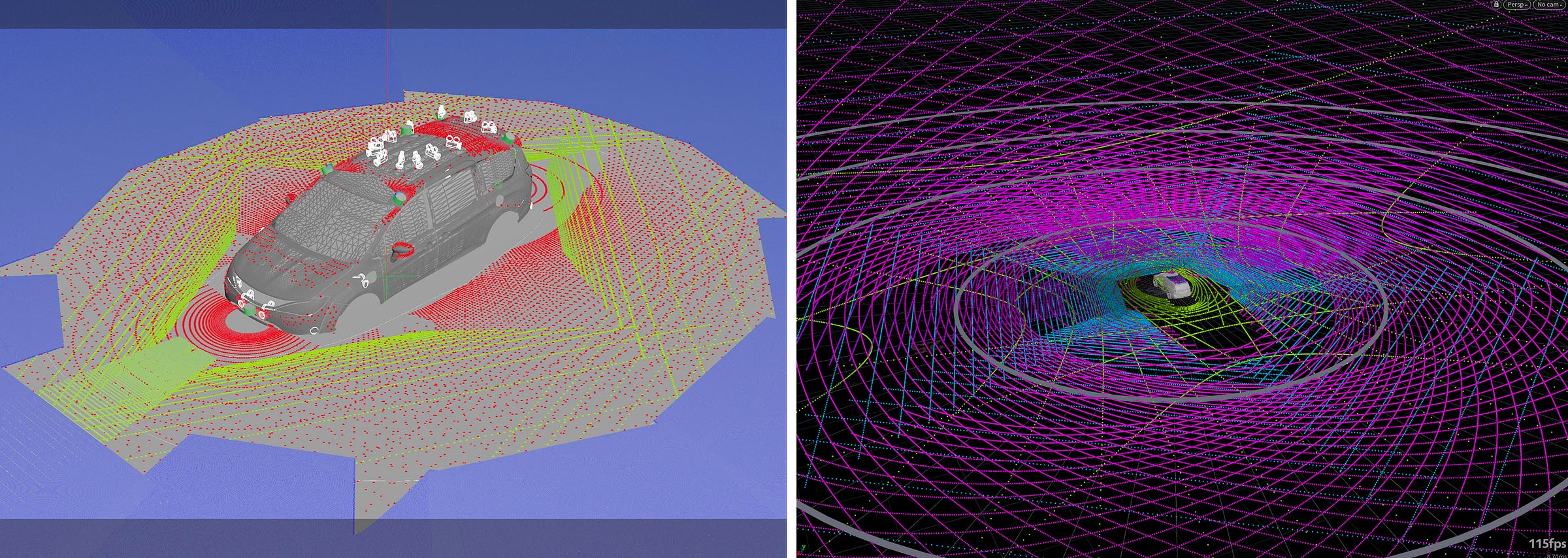

At Level 5 we opted for a sensor-fusion platform. That is combining RGB cameras with lidar and radar sensors. I won’t go into the details too much but at a high-level lidar gives you two important data points. First, it gives you time-of-flight. That is how long it takes for a photon to travel to and from an object. This gives you a reasonably precise prediction of distance and allows you to reconstruct objects in 3D space. The second data point is reflection grade. This gave us an indication of what kind of material the object was made of. One can argue (as Elon has) that Lidar is redundant if camera-based neural networks are good enough to accurately predict the world. Just infer the scenario from moving pictures. That’s true in theory. And there are trade-offs. Specifically, when you include more sensors the BOM cost goes up, you need more compute, which requires more power, which requires more cooling, which makes the car heavier etc. The whole thing becomes more of a science project than a production vehicle very quickly. On the other hand, lidar offloads a lot of the risks in just relying on cameras. It’s a more robust approach to making a robot car sense its world as it gives you higher-fidelity, time-of-flight data, sensor redundancy, and more robust predictions in rare scenarios. It’s worth getting these types of decisions right early when you start designing in any hard tech field. Do you really need that extra sensor? And what trade-offs are you willing to make?1

The video above shows a lidar scene in 3D. Our SLAM team in Munich had made some really clever software to reconstruct a scene from lidar point-clouds colored by calculating the overlaying pixel color from the RGB camera image. It made understanding and annotating the scene much easier.

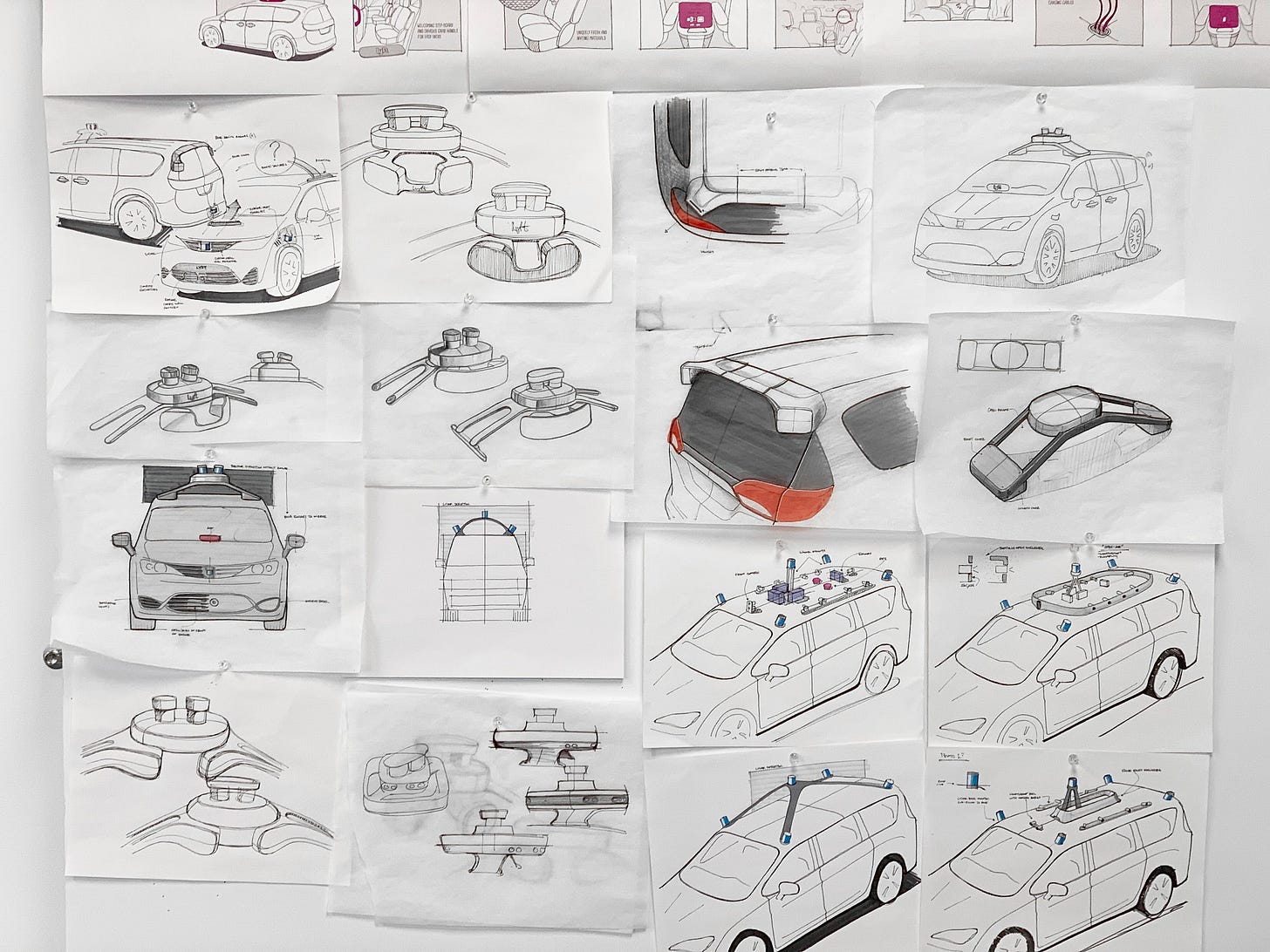

L5 had acquired several hackable Ford Fusions as the base vehicle. That meant we could concentrate our efforts on sensors, computers, and software. Thus, the first design challenge was to create a sensor mount for the roof-top of the car to house all the expensive sensors. The first iteration of this design didn’t work. The plastics were glossy black and would soak up the Californian sun and thus overheat the electronics. The build was also too complex and made it maddeningly difficult for the Mechanical and Electrical Engineers to swap out components and service the rig. Not great for a prototype vehicle. But v1 is about learning. We learned we needed different materials, better cable management, simpler sensor swap setups, more cooling, and protection for the cameras.

The second version solved these issues. Similar footprint, but much improved internals, finishes, and sensor configurators. The v2 was the workhorse of the fleet. We built 24 Ford Fusion prototype cars in total. These were never meant to be production cars but simply a way to get started collecting data from the real-world quickly.

Hardware is hard: Virtual sensor configurator

The sensor team was testing lots of different sensors and placement configurations. They complained it was really cumbersome to reconfigure, calibrate, and test a new sensor setup. In essence every time they moved a sensor, e.g. to get better coverage in blind spots or see potholes or traffic further ahead or to correct for lens flaring, they had to physically move the sensors, test and recalibrate the whole setup. They needed a rapid iteration method.

A brilliant designer on my team realized we could create a virtual sensor configurator setup to test coverage before doing any physical mounting and calibration. Borrowing ideas from the film industry he teamed up with the Sensor team and developed a virtual sensor configurator tool to speed up iteration. In the tool you could place the cameras, lidars, and radars. Each sensor in the tool had built-in lens angles, distortions, field-of-coverage, fall-off, and distance metering so we could accurately model and calculate the coverage and ideal placement much faster. This sped up the cycle by almost 4×.

Visualize in real-time

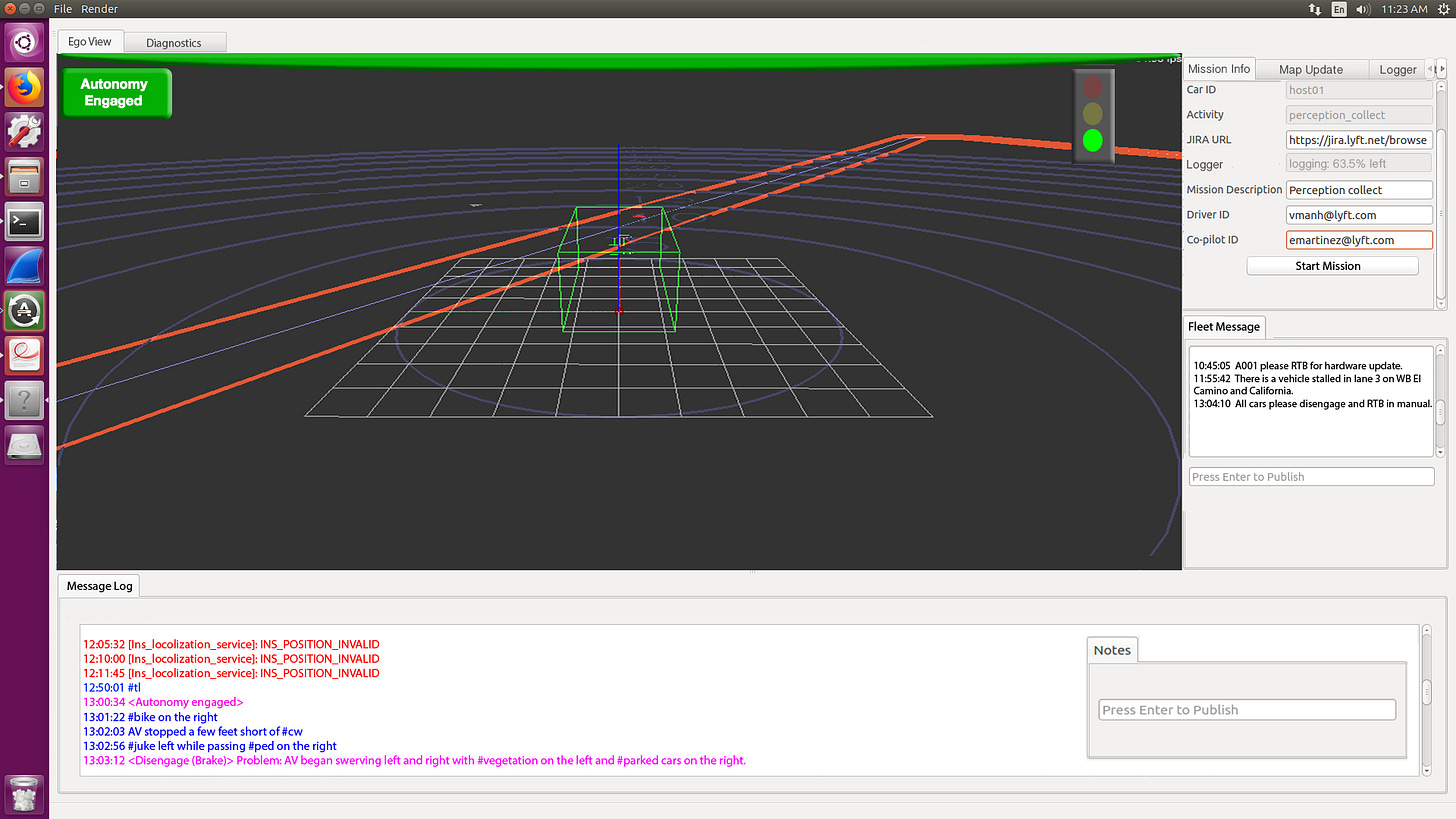

The second challenge came in the form of a live feed for the safety drivers. We had 2-3 people onboard the cars when we did “data collections” and safety testing. The first was the driver. A professionally trained driver whose job was to monitor the car and take over in case the system messed up. The second was the co-pilot whose job was to survey both the road traffic and model behavior. For instance making sure the ML model was registering the correct objects like stop signs and pedestrians. He would face a monitor with various information and a feed of what the car was seeing in real-time. Sometimes, an engineer from the ML team would also monitor the model, review the latest build on the road, and look for software bugs and overall model performance. He would typically sit in the back and look at the live feed of the model or interact with the co-pilot to verify a given scenario.

The UI the engineers had whipped up left a lot to be desired. It was hard to see on the road with excessive glare on the dark screen, lots of small menus, no clear indicator whether autonomy had been disengaged or not, and the scenario details were hidden in obtuse logs or submenus.

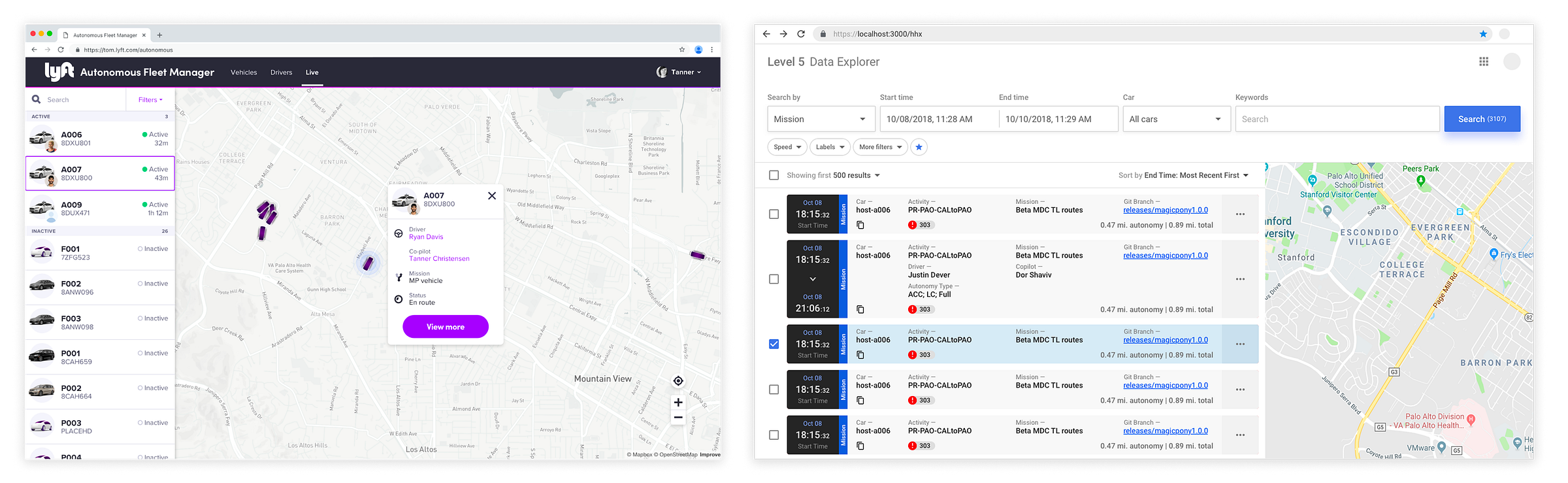

CarViz, as we named it, became a central element in how the entire team understood the development challenges. After about 1 year we had over 100 engineers spread out across five offices in San Francisco, Palo Alto, Seattle, Munich, and London. We were dealing with hardware, software, ML training, mapping, data annotation, safety testing, and operations.

The role of design was not only to build better internal tools to wrangle the complexity but also to create simple and compelling visuals that would rally the distributed teams and allow leadership to communicate credibly to the press and the public. Never underestimate a good design asset.

Scaling up data annotation and testing

CarViz was the first in a series of tools that helped manage the complexity as we scaled up. It first and foremost made the experience for the pilot and co-pilot and broader ops teams faster and safer. A lot of the communication and coordination between teams became painfully complex; loading a new model on the car’s computers, synchronizing it with the right firmware and new sensor configurations, loading the right scenario to be tested, planning a route with driver and co-pilot, and keeping it all in sync. The complexity required us to zoom out and rethink the problem. When I suggested we break down the work tasks into simpler, small apps to help manage them, I often met pushback from the engineering managers in the form of “we don’t have time!” to which I replied that was like saying we were “too hungry to eat”. The compounding complexity was creating bottlenecks everywhere. In the end we solved it through a series of smaller tools that each talked to each other on the backend.

We started doing a lot of driver collections. The data we collected from our cars would need to be processed and annotated. The quality of any ML system is only as good as its training data. And for self-driving cars it meant lots and lots of high-quality annotated scenarios from the real world. Back then we didn’t have access to the auto-labeling tools that exist today. So we had to start from basics and build the tools ourselves. In practice it meant we had to hire a team to review the footage and pin-point what objects and behaviors were in the recorded footage, then categorize it and label it studiously and, only then, upload for training better models.

Our tools had a material impact. The Fleet Manager drove down the cost of vehicle onboarding by 85% and the lidar annotation tool reduced the estimated cost of 3D annotation work from $2M to $600.000 in the first year alone. We also partnered with scale.ai for annotation services. We were one of the first teams to bet on the newly founded startup. Data labeling turned out to be a big business.

Safety first

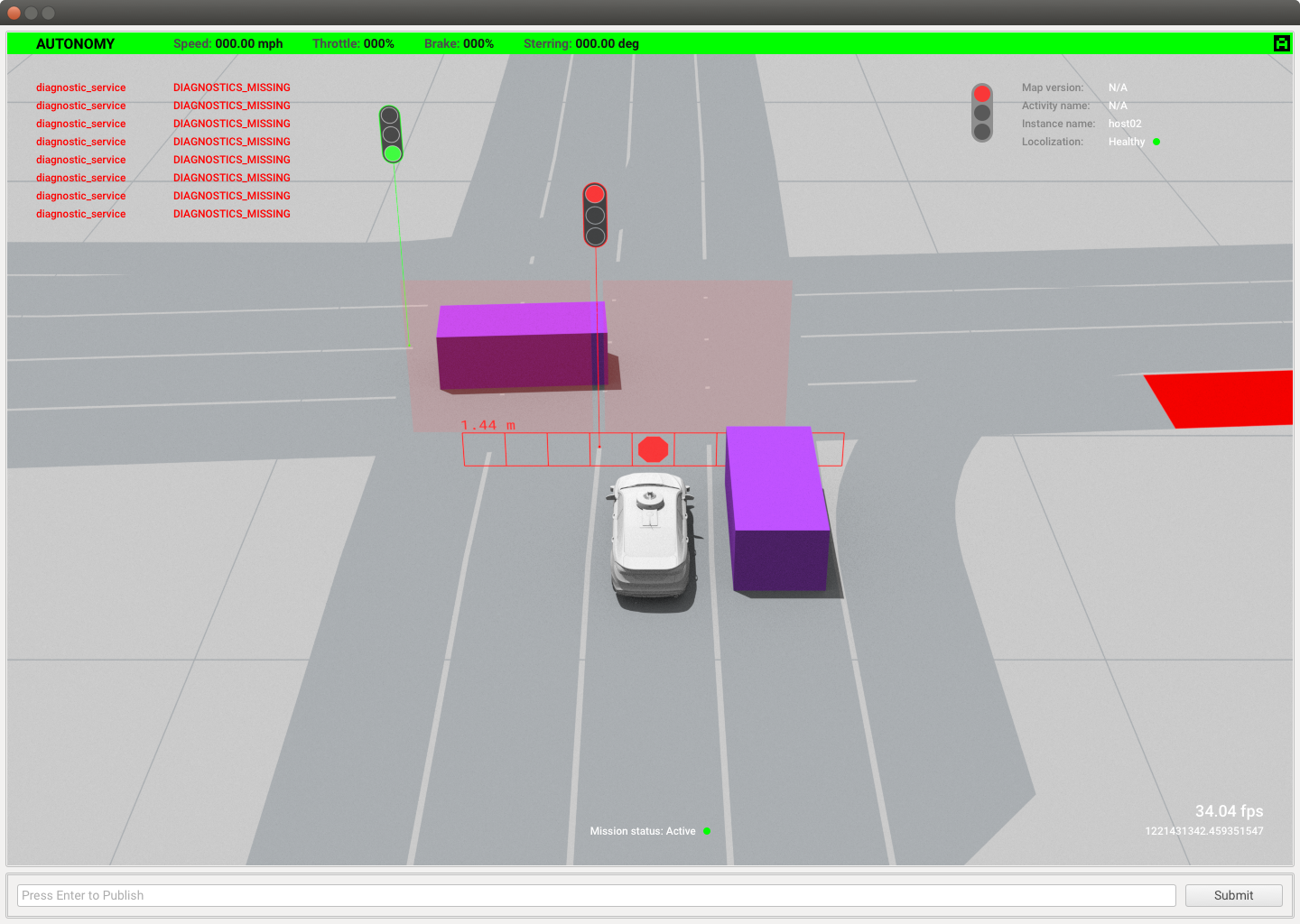

We also started doing a lot more safety testing. Specifically, we embedded a Researcher on the driver team to monitor, test, and evaluate areas we could improve and make sure we were as safe as possible. We even built test tracks to drive on closed circuits and evaluate both driver reaction times and the full technology stack (car controls > sensors > compute system > models < > driver take-over). Below is an example where we deliberately inject an error state into the system to cause the car to swerve hard into the left lane. Obviously the car is not supposed to do this but we wanted to test how the system would react, including how fast the safety driver could gain control of the car. There’s no substitute for real-world data.

One key challenge all self-driving car companies face is rare scenarios. Think about construction work, ambulances coming fast from behind, kids out for halloween, or weird accidents. Even simple things like yellow traffic lights we didn’t really have enough training data for in the beginning. Of course, the ideal is to gather all these rare scenarios from the real world. But this requires millions of miles driven. A heavy lift for a cash-strapped upstart like Lyft.

We experimented with a couple of novel solutions. One of which birthed the Synthetic Scenario tool. It was a software tool that stitched 3D virtual objects into the existing footage, mapped the correct lighting and shadows, and then rendered out the video with, say, traffic cones, yellow lights, or road signs that weren’t originally there. It was a hack to increase the occurrence of rare objects and scenarios into the training data before waiting for real-world collection. Today, Nvidia and others are building fully synthetic world models to solve this exact problem. But back in 2019 we didn’t have such luxuries. Besides there’s something to be said about being scrappy and just creating the fast and good enough solution and move on. Momentum matters.

The Synthetic Scenario tool never made it to production sadly. It was hard to implement reliably and hard to justify the engineering resources amidst the fast-moving chaos of just trying to get the current generation of models to work reliably. But it did prove a point. The design-first prototype tool we built did work; we tested it by creating 500 synthetic frames of yellow traffic lights. Stitched them into video and re-trained the object classifier for traffic lights. We then tested it to see if it had better prediction for yellow colors of traffic light. It did. It improved object detection by about 8% and reduced false positives by 12%. Pretty good gains for a simple design tool.

Vehicle experience for production

All the internal tooling and data annotation workflows built a foundation to make the cars sense, collect data, and allow our teams to annotate and train on that data. But we were still making prototype vehicles. The next step was to design a car experience for the masses.

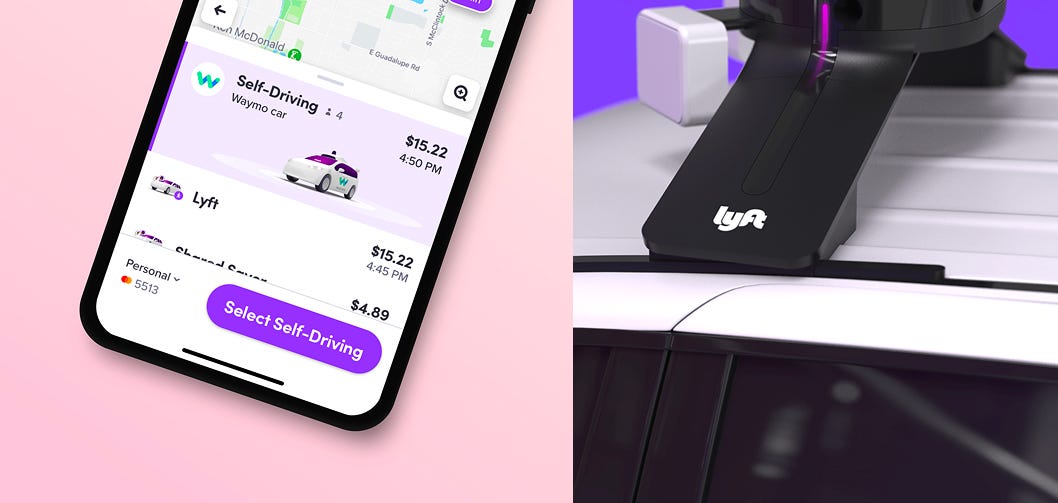

The Chrysler Pacifica became the vehicle platform of choice. For one it had a much larger trunk to house all the compute- and cooling-systems, and the larger cabin made it easier to place screens and internal sensors, and, importantly, carry more riders. Besides, Waymo had already shown this platform worked well. We now had to design a new sensor pod, interior experience, and app and partnership program to get it to the masses. We had 6 months. Easy!

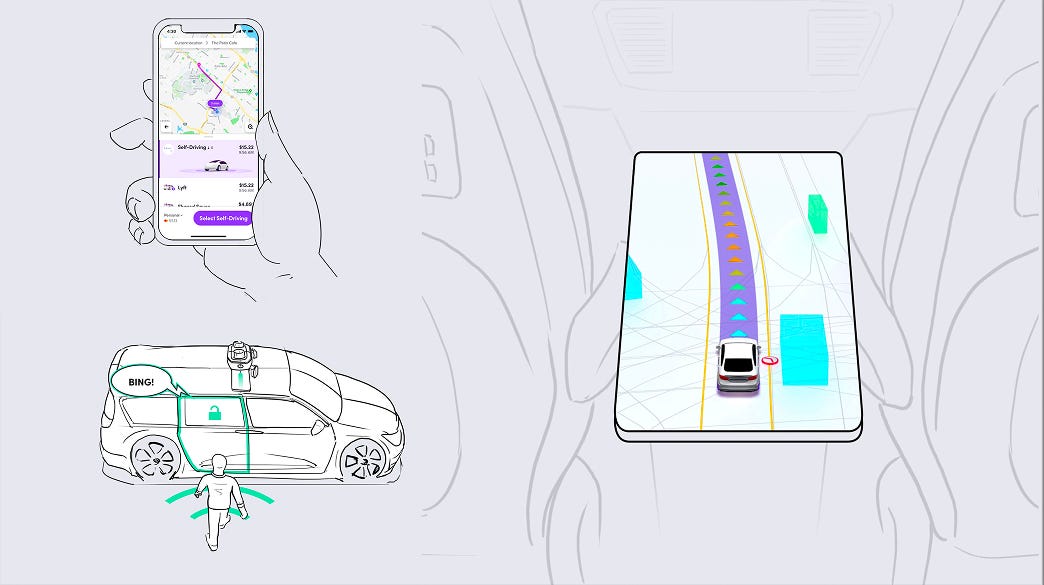

We experimented with user experience including entry lighting, sound design, rooftop lighting (to easily show which specific vehicle was yours), in-car infotainment system to make the passengers feel in control and safe. One of my favorite inventions was our novel approach to unlocking the vehicle. We used the lidar-data and mobile app’s accelerometer data in-sync to allow the car to identify the right person to enter the car. We designed support systems for remote operators to take control of the car and communicate with the passengers. And we partnered with the marketing teams to level up our branding for wider public release.

Below, a CNBC video of the AV lab up close in 2020.

Tell a strong story

There were many moving parts. After about 2 years we were servicing multiple internal tools, research programs, hardware lines, and two vehicle platforms. We had partnerships with OEMs and made assets for marketing, all the while we had to keep a consistent design direction and high bar for everything we did.

In 2019 I did a talk at Maersk explaining how we made the self-driving car and pondering how AI might shape the future of transportation. My aim was to show how AI is enabling us to move computing out of the closed-world environments and into the real world. AI in the wild.

I firmly believe design can be a multiplier. Done right, it’s a powerful way to convince a wide audience about the importance of the goal. I’m obsessed with the idea of how design can change the world.

Design is more than art or product finish. It’s really problem solving at scale. But none of it matters if folks don’t get it. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry is credited with saying,

“If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the endless immensity of the sea.”

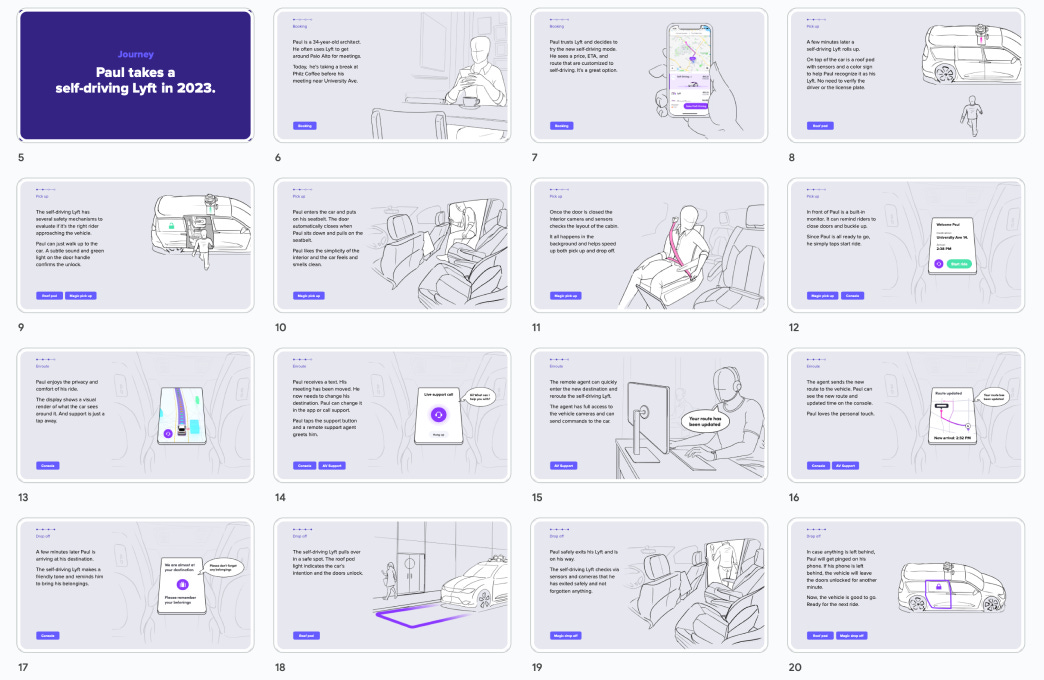

We needed the Level 5 team to yearn for our wonderful self-driving future. We needed a singular vision. But visions aren’t made by individual mocks or glossy renders. You need a strong story. A story that aligns people and tilts perspectives. It’s a slight-of-hand that looks effortless when it works. We needed to make a vision for the whole endeavor that was compelling enough that once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Our audience was the whole Level 5 team and Lyft leadership. For a story like ours we needed to strike the right balance between abstraction so people would suspend their disbelief and not hark on the individual details, yet concrete enough so everyone would walk away with the same imprint in their minds. If it was too goofy it wouldn’t garner excitement or be taken seriously. If it was too polished and high-production it would look detached from reality and also not be taken seriously by the engineers tasked with shipping the code and hardware. Besides, we had extremely limited resources so we made a collection of hand drawn scenes that focused on all the various components we were shipping and how they fit together in an simple story from our fictional rider’s perspective. We presented it at L5 all-hands and widely shared the deck that included lots of background research, demos, links to PRDs, trackers, ops reviews, and company goals.

I talked to all the individual team owners and asked for feedback and what it would take to ship “something like this”? (A little give on the leash is a good thing if you want to get things done.) The team and I drove multiple conversations around the company about why we, Lyft Level 5, deserve to exist and what made us special. It sounds silly explaining it out loud but it’s truly important to garner attention in the right way. To allow people to adopt a new view without being told they have to. Nobody likes being sold to. But everyone loves a good story. At this point Lyft had more than 5000 employees and a company is not a monolith but made up of fractions of people. Those people drive decisions and a subset of those people take action. Get your vision in front of the people who take action and it will happen.

After 2 years we had shipped 16 software products, 14 industrial design projects, run 4 research studies, and produced a single vision. To everyone’s credit our small but mighty AV Design team of five people got a lot of support and attention in the company.

We celebrated the 2 year anniversary with a fun design reel (video above, sound on). This wasn’t shared widely at Lyft and really only meant for the Lyft design team. But it’s important to celebrate good work. Especially when you’re moving fast. We had a dual mandate; first, design the internal tools to make us go fast, and second, design the exterior and customer experience to win in the market. We achieved both.

In 2021, Lyft sold Level 5 to Toyota’s Woven Planet division for $550M. Lyft was going public and the heavy expenses associated with developing robot cars were hard to justify to public investors at the time. Today, the self-driving car revolution looks closer to reality than ever. Tesla is launching Cybercabs and Waymo is already growing rapidly in cities like San Francisco and Austin. But back in 2018 the road was less traveled and the solutions much less obvious.

Even though the Lyft autonomous car never happened on a grander scale, the work we delivered was important and meaningful. We faced a lot of crazy challenges and working with incredible people is always inspiring. I’m proud of the work we did. Never underestimate the power of design.

For any ML training problem, like the self-driving car, one core bottleneck is how you get a continuous stream of diverse and high-quality training data? Tesla made the choice of camera-only to reduce the cost of the entire vehicle which allowed them to ship cars to the masses. That in turn lets them collect many more miles of real-world scenarios, albeit at lower data resolution than for instance Waymo’s lidar-kitted cars. Tesla effectively offloaded the cost of driving, parking, fuel, insurance, depreciation, and data collection onto their customers. Smart if you can do it. Almost the entirety of the AV industry went with sensor-fusion and professionally trained driver collections though. As did Level 5. Fewer cars but with more robust data streams for more robust scene reconstruction and redundancy. Safer but much slower to scale.